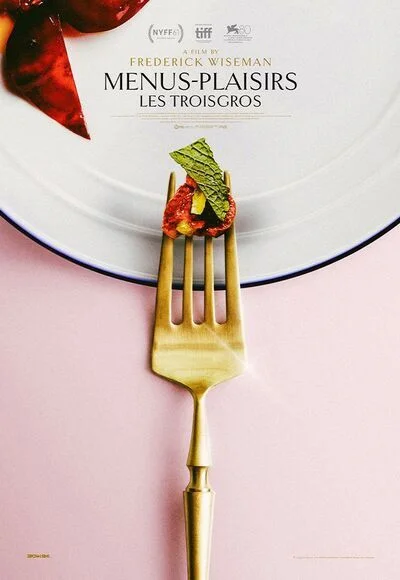

‘Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros’ Review 2023

The Art of Culinary Evolution: A Cinematic Exploration of ‘Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros’ by Frederick Wiseman

The venerable 93-year-old documentary maestro, Frederick Wiseman, is frequently hailed as a filmmaker renowned for capturing the intricacies of institutions, be they large or small, and illustrating their transformative journeys over time. Whether exploring an army base, a mental hospital, a domestic violence shelter, a quaint town in Maine, a neighborhood in Queens, or the bustling New York Public Library, Wiseman’s distinctive focus on institutional dynamics is undoubtedly the prominent thread woven through his extensive body of work.

However, Wiseman’s value extends beyond mere depiction; it lies in the simplicity and purity of his filmmaking. The true essence of exceptional documentaries goes beyond mere exposition or storytelling. Instead, they encapsulate life’s moments and unveil elusive, perhaps previously unspoken truths about existence. They enable a fresh perspective, encouraging viewers to perceive with new eyes and comprehend aspects they may have overlooked or taken for granted. Moreover, these documentaries often exhibit keen insight into the intricacies of creation, whether showcased through the endeavors of artists, as seen in a series of French documentaries like “Crazy Horse,” “Ballet,” and “La Comédie-Française ou l’Amour joué,” or in the dedicated efforts of workers and citizens in other films striving to serve their clients or community, merely navigating the challenges of the present year and anticipating the next.

In the documentary “Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros,” spotlighting a restaurant in France, Frederick Wiseman’s multifaceted talents come to the fore, showcasing one of his most straightforward yet profoundly layered works. It stands among the great films dedicated to the realm of food and cooking, rivaling the likes of “Big Night” and “Tampopo.” Functioning as an exemplary “process” movie, it unravels the intricate inner workings of a fine dining establishment – from the initial acquisition of produce, meat, and fish to the meticulous stages of preparation, plating, and service. Beyond its culinary focus, the film delves into the familial dynamics and the intricacies of family-run enterprises. Yet, perhaps most subtly and remarkably, it serves as a contemplation on the act of truly looking at things, appreciating them for what they are. This ranges from a display of carrots or radishes in a market stall, a blossoming shrub in a field, a herd of cows grazing, to a bustling hive of bees, and the intricate choreography of employees and supervisors gracefully navigating a restaurant kitchen.

The primary setting of the documentary is “Le Bois sans Feuilles,” meaning “The Forest without Leaves,” a prestigious restaurant boasting three Michelin stars. Originally situated in an urban locale in Roanne, adjacent to a train station where it thrived for decades, the restaurant underwent a significant shift in 2017. It relocated to a manor in nearby Oaches, embracing a more “countryside” ambiance. Managed by the Troisgros family, proprietors of two additional local restaurants, the film encapsulates Frederick Wiseman’s characteristic fascination with the evolution of institutions over time.

The narrative unfolds through the lens of the Troisgros family, with a focus on the present patriarch, Michel, and his designated successor, César. The film subtly captures the interplay of generations and the intricate dynamics within the family-run establishment. Notably, it briefly touches upon Michel’s younger son, Léo, a chef at another restaurant. Léo’s exasperation surfaces when his father unexpectedly alters the sauce for a dish he has meticulously perfected over three weeks, adding an additional layer of familial and professional tension to the unfolding narrative.

It takes some time to discern the familial connection between César and Michel, who primarily interact in the roles of employer and employee, maintaining a cordial and mutually respectful dynamic. True to Frederick Wiseman’s distinctive approach, the documentary abstains from conventional elements found in many documentaries. There are no talking head interviews, no identifying “chyrons” or titles providing names and positions, and no voice-over narration—deviating from the now-common documentary conventions regardless of subject or style.

However, Wiseman employs a clever workaround to adhere to his “no narration” rule. Instead of direct commentary, he often captures a subject requesting another person to verbally explain a particular idea or process. This approach allows the audience to observe and listen, maintaining the immersive and unobtrusive style characteristic of Wiseman’s filmmaking.

On occasion, a restaurant employee or customer may mention someone’s name, although such instances are infrequent. Frederick Wiseman deliberately constructs the narrative to encourage viewers to appreciate individuals solely through their actions and words, emphasizing their connections to the spaces they inhabit, whether for work or residence. The filmmaker invites the audience to infer the characters’ broader relationship with the world based on their observed behaviors.

Throughout the film, Wiseman incorporates mini-montages between scenes or sequences. These montages feature tight closeups and lingering wide shots, allowing ample time for the audience to immerse themselves in the visual intricacies of each image—the texture, color, and content. The editing introduces movement, often achieved by selecting a sequence of shots where individuals traverse the screen laterally, all moving in the same direction. This technique adds a dynamic visual element, enriching the audience’s engagement with the film’s visual tapestry.

However, the predominant approach in “Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros” involves Frederick Wiseman and his cinematographer, James Bishop, carefully selecting vantage points to observe groups of two, three, or more individuals engaged in various activities. They capture these moments and let them unfold organically, allowing the audience to witness the natural progression of events. Each of these observational episodes possesses a richness that renders it akin to a self-contained short film—sometimes informative, at other times subtly humorous or empathetic.

For instance, there’s a segment where diners receive an explanation about the use of sulfite in winemaking. Another part features a cheesemaker guiding restaurant staff through his factory, elucidating the chemical processes involved in ripening cheeses, emphasizing, “Each cheese has its moment of truth, and that’s when you sell it.” A farmer engages Michel in a discussion about the lactation cycles of goats and how it impacts his business. Additionally, there’s a captivating sequence illustrating the extraction of honey from a beehive, adding diverse layers of insight and intrigue to the overall narrative.

The manner in which Wiseman captures, edits, and situates these moments actively encourages viewers to establish connections between disparate parts of the film. For example, the beehive scene might prompt reflections on the wide shots of the kitchen, where the orchestrated movement of “worker bees” collaboratively carries out their tasks. Yet, Wiseman’s approach is rooted in inference; he never spoon-feeds information or compels the audience with a directive hand. There’s no grabbing the back of your neck, turning your head, and dictating, “Now look here.” It’s not a critique of other filmmaking styles—in fact, there’s value in various approaches. However, Wiseman’s distinctive refusal to adopt such overt techniques contributes significantly to setting his films apart.

Another distinctive aspect of Wiseman’s films is their often considerable runtime, a characteristic that demands a certain surrender from the viewer. Scenes unfold at their own pace, guided solely by the film’s internal rhythm. There’s no clock-watching involved, and as an audience member, you’re encouraged not to either. Maintaining focus during scenes that may seem extended allows you to discern a deliberate strategy at play. The extended durations serve to facilitate a nuanced, moment-to-moment evolution within the narrative—observing how a conversation or exchange initiates in one manner and transforms into something entirely different over time.

Take, for instance, a protracted scene around two-thirds into the film where Michel indulges in a dish overseen by César. The ensuing lengthy discussion revolves around Michel’s perception of what the dish lacks—an element of visual appeal rather than a deficiency in taste. Michel acknowledges the absence of “hangers-on softening the taste of the sauce,” describing the flavor as “very nice.” However, he raises the crucial question, “but to look at?” The restaurant’s acclaim hinges significantly on its remarkable presentation. Each dish is meticulously plated, resembling a painting within a circular frame. Every element on the plate is not only well-balanced in composition and color but also thoughtfully aligned with taste and texture, avoiding any conflict. One can sense César’s initial resistance to these remarks, followed by a subtle acquiescence. Whether this shift occurs because he recognizes his father’s insight or due to the hierarchical dynamics between them is left for the audience to interpret.

At a certain juncture, Michel reflects on the restaurant, noting that “it’s always in movement.” His remark encompasses not only the dynamic nature of the menu and the physical space but extends to the lives of everyone laboring within its confines and the artistic process itself. Wiseman, aligning with the belief that food can serve as an artistic medium, views it as inherently ephemeral, akin to theater—an art form he is also involved in. In the culinary realm, you craft something visually stunning, only to witness its gradual destruction as it is consumed. The daily life of a restaurant embodies a continuous cycle of creation and destruction.

This film prompted a realization about the contemporary phenomenon of people capturing images of their food, facilitated by modern technology that allows for instant results. It becomes evident that individuals desire a record of these delectable or aesthetically pleasing objects that are destined to vanish, capturing a visual memory before it succumbs to the act of consumption—a manifestation of the inherent cycles of creation and destruction that define the realm of restaurants.

Now playing in theaters.

Film Credits

By: M Z Hossain, Editor Sky Buzz Feed